Dutch tax insights in debt restructuring cases

As a result of interest rate hikes over the past years, together with a further limitation of interest deductibility for tax purposes, the cost of debt has put increased pressure on the financial stability of companies. Several highly leveraged companies are consequently in financial distress and debt restructuring may be crucial to avoid bankruptcy in such cases. As such debt restructuring could have significant tax consequences, it is important to consider these at an early stage of the debt restructuring process. In this blog, we will highlight certain focus areas from a Dutch tax perspective in debt restructuring cases involving a Dutch debtor, also considering creditors holding or obtaining an equity stake – directly or indirectly - in the borrowing entity.

1. Dutch conditional withholding tax

To combat tax avoidance and to prevent the Netherlands from being used as a conduit state, the Netherlands levies in certain situations a conditional withholding tax (CWHT) on (deemed) intragroup interest payments since 1 January 20211. The Dutch CWHT rate equals the highest Dutch corporate income tax rate, which is 25.8 percent (2024). The Dutch CWHT applies only if certain conditions are met. The first condition is that a payment is to be made to a related entity. The second condition is that such related entity resides in or acts from a so-called low tax jurisdiction for Dutch tax purposes2 or is considered to be part of an abusive structure (see certain (deemed) abusive structures below).

The term ‘interest’ should be interpreted broadly and includes any consideration payable in relation to a loan agreement. It should therefore also be considered that fees payable because of the debt restructuring may also be in scope of the Dutch CWHT. If no interest is due and payable in a calendar year (e.g. in the case of a PIK loan), interest will be deemed to be due and payable at the end of each calendar year.

Condition (i) – Related Parties

As stated above, the first condition is that a payment is to be made to a related entity. ‘Related’ in the context of the Dutch CWHT means that the recipient should – alone or as part of a collaborating group – have a ‘controlling interest’ in the debtor (or vice versa). The definition of a controlling interest is derived from EU case law and is, in short, present in the case of a direct or indirect holding giving the relevant party definite influence over the company's decisions and allowing the holder to determine the company’s activities. Such control could arise, for instance, in the context of an enforcement of security rights. An interest is in any event considered controlling if it represents more than 50% of the voting rights in a company under the company's articles of association.

Generally, Dutch CWHT is not an issue from the start of the financing, as there is rarely a controlling interest. However, it may become relevant in the event of a debt restructuring if creditors obtain control or obtain a direct or indirect equity stake in the borrowing entity, for example because of an event of default. In such a situation, several Dutch CWHT aspects should be considered, which we will address in more detail below.

Cooperating group (samenwerkende groep)

As mentioned above, the Dutch CWHT applies only to interest payments between related entities. If a creditor does not have a qualifying interest on a stand-alone basis, it may still be deemed related based on the presence of a cooperating group. The cooperating group concept has been derived from a specific interest deduction limitation rule which was specifically introduced in 2017 to capture abusive structures that were created to avoid the applicability of this rule. In this light, the Dutch legislator deliberately did not choose a statutory definition of the term ‘cooperating group’ and application depends on the facts and circumstances of the individual case. To date there is limited guidance on the scope of a cooperating group. It therefore remains unclear in practice whether a group of creditors working together to safeguard their investment from bankruptcy falls in scope of the concept of a cooperating group. After various signals emerged from practitioners that the effect of a cooperating group is unclear in many cases and affects debt restructurings, the Dutch Ministry of Finance announced that a new and distinct group concept would be introduced to replace the current concept of a ‘cooperating group’ in the Dutch CWHT. The new rules are expected to be published on Budget Day (17 September 2024) as part of the 2025 Tax Package.

Condition (ii) – Acting in or from a Dutch low tax jurisdiction or abusive structures

In principle, the Dutch CWHT is aimed at avoiding tax structures with low tax jurisdictions. However, to avoid abuse, certain other structures are deemed abusive and therefore may be in scope of the Dutch CWHT.

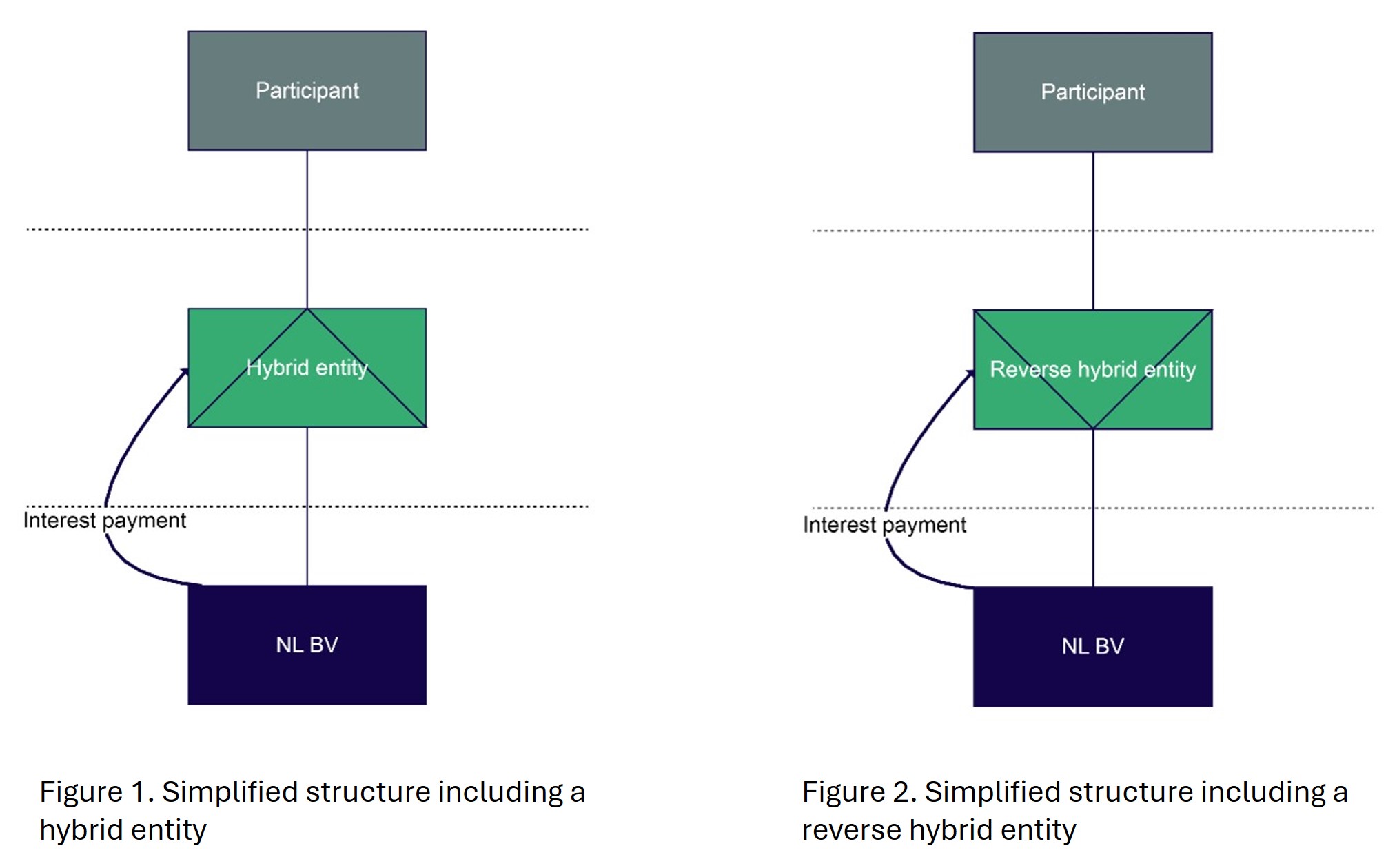

Reverse hybrid or hybrid entities

Subject to certain escape rules, payments to hybrid or reverse hybrid entities may fall in scope of the Dutch CWHT. This anti-abuse measure is aimed at targeting structures where there is no inclusion of the interest income in the taxable base of either the direct recipient or the ultimate participants.

An entity is considered a hybrid for Dutch CWHT purposes if it is non-transparent from a Dutch tax perspective, but tax transparent from the perspective of that entity’s jurisdiction. We refer to figure 1 below for a simplified structure involving a hybrid entity. An entity is considered a reverse hybrid for Dutch CWHT purposes if it is tax transparent from a Dutch tax perspective, but non-transparent from the perspective of the jurisdiction of the entity’s participants. We refer to figure 2 below for a simplified structure involving a reverse hybrid entity.

In practice, it may be complicated to determine whether the recipient of the interest is considered a hybrid or reverse hybrid under Dutch law. One relevant factor in making this analysis is how the recipient entity is classified for Dutch tax purposes (i.e. as transparent or non-transparent). It should be noted in this regard that the Dutch tax classification rules will significantly change as of 2025 and may lead to a different outcome as to whether a recipient entity is considered a hybrid or reverse hybrid entity and possibly in scope of Dutch CWHT. For further background information on the Dutch classification rules as of 2025 we refer to our Tax Alert of 4 April 2024. The analysis of whether a recipient entity is a hybrid or reverse hybrid also depends on the tax classification of the recipient’s jurisdiction (if the Netherlands views the entity as a non-transparent entity; see figure 1 above) or the jurisdiction of that entity’s participants (if the Netherlands regards the recipient as a tax transparent entity; see figure 2 above). If it is concluded that payments are made to a hybrid or reverse hybrid entity, such payments may in the end, however, not be in scope of the Dutch CWHT if the escape rules set out in the Dutch CWHT Act apply (e.g. if the ultimate investors are deemed good investors for purposes of the CWHT).

Conduits

Also payments to non-hybrid entities not residing in or acting from low tax jurisdictions may fall in scope of the Dutch CWHT. However, this only is the case if the recipient is considered a ‘conduit’. An entity is considered a conduit if it is interposed to avoid Dutch CWHT and is artificial. If an entity meets all relevant Dutch substance requirements, such as having qualified employees for proper implementation and registration of the transaction to be entered into and local payroll expenses, and having office space at its disposal, it will be presumed not to be a conduit, but the Dutch tax administration may nevertheless dispute this presumption. The same applies to a taxpayer that does not meet all Dutch substance requirements but can demonstrate that it has economic purpose and is not artificial.

In practice, creditors are often organised as collateralised loan obligation (CLO) type entities. In short, a CLO type entity holds a wide variety of investments for a wide group of investors. Although such CLO type entities generally do not meet all relevant Dutch substance requirements (such as having an office space at their disposal), there are good arguments as to why such entities should not be considered artificial, given their active management and economic purpose, among other things. However, there is not yet any relevant case law, any view of the technical committee (kennisgroep) of the Dutch tax administration or any other guidance that endorses this position.

Tax treaty relief?

If a creditor is in scope of the Dutch CWHT, it should also be considered whether a tax treaty is in place that may provide relief. If a tax treaty is in place, it may protect a creditor from Dutch CWHT if the tax treaty provides for a zero (or reduced) withholding tax rate on interest. If a tax treaty contains a principal purpose test (or a similar clause tackling abuse)3, the Dutch government is of the view that the Dutch CWHT can be fully levied, as this withholding tax is based on anti-abuse rules. As a result, such creditor(s) will in the end not be able to benefit from treaty protection. Please note that the Netherlands will not consider a tax treaty partner as a low tax jurisdiction for purposes of the Dutch CWHT in the first three calendar years after that treaty partner is added to the list of low tax jurisdictions for Dutch tax purposes.

Certain formal aspects of the Dutch CWHT

The Dutch CWHT must be withheld by the withholding agent (i.e. the Dutch debtor) on interest payments made to the creditors. The Dutch CWHT return must be filed once a year and is due one month following the end of the calendar year in which the Dutch CWHT has become or is deemed to have become payable. If no Dutch CWHT has wrongly been withheld and remitted to the Dutch tax authorities, the Dutch tax authorities may impose an additional tax assessment at the level of the target or at the level of the creditor(s). It should be noted in this regard that the Dutch CWHT Act does not obligate the taxpayer to provide (accurate) information to the withholding agent. However, the other side of the coin is that the withholding agent is not obligated to investigate whether the information received from the taxpayer is accurate. It can be derived from case law, however, that this does not mean that all information provided may be assumed to be true. The Dutch tax authorities have five years after the tax return filing date to impose an additional tax assessment.

2. Debt waiver exemption

Cancellation of debt is often considered if a debtor is in financial distress. A waiver of debt may lead to taxable income at the level of the debtor. If such waiver occurs for business reasons, Dutch tax law provides for a debt waiver exemption if certain specific conditions are met. If the debt waiver exemption applies, no Dutch corporate income tax will be due as a result of the waiver of debt. The key conditions are that the receivable is not realistically collectable from a creditor's perspective and that the creditor expressly waives the receivable. The Dutch debt waiver exemption applies only to the taxable income exceeding the available tax losses (i.e. all tax losses should be utilised first). As from 2022, the tax loss carry forward rules for corporate taxpayers have changed, as a result of which the tax loss carry forward is limited to 50% of the taxable profits to the extent that these exceed EUR 1 million.

We have illustrated this in the following example.

The taxpayer has a waiver profit of EUR 10 million and tax loss carry forward of EUR 10 million. As a result of the new rules, only EUR 5.5 million may be set-off (i.e. 1 + 50% of 9 million). The taxable amount in the case at hand is EUR 4.5 million.

The Dutch debt waiver exemption stems from the idea that debtors in an insolvent position should not be paying tax on waived debt, but should utilise their tax losses (to the extent available). However, as a result of the change in the law as of 2022 (as described and illustrated above), taxpayers may end up in a tax paying position (i.e. if the waived amount exceeds EUR 1 million). The Dutch Ministry of Finance recently announced that it would fix this unintended outcome of the concurrence between the Dutch debt waiver exemption and the tax loss carry forward rules. However, it is still unclear how exactly this will be fixed and whether this proposed amendment will have retroactive effect.

Pillar Two implications

If a debtor is in scope of Pillar Two, i.e. in short, if its consolidated group revenue exceeds EUR 750 million in at least two of four consecutive years, it should also be taken into account that the Minimum Tax Rate Act 2024 (the Dutch implementation of Pillar Two, Wet minimumbelasting 2024) includes a debt waiver exemption that deviates from the Dutch debt waiver exemption described above.

The objective of Pillar Two is to guarantee a minimum level of taxation by introducing rules that grant jurisdictions additional taxation rights, and to limit tax competition between jurisdictions. Based on the Pillar Two rules, a minimum effective tax rate of 15% has been introduced resulting in additional tax to be levied if the effective tax rate is less than 15% (a ‘top-up tax’). The top-up tax will be calculated based on, among other things, the so-called ‘qualifying income’. Certain corrections may be made to make sure that the qualifying income is considered at arm's length for Pillar Two purposes. One of these corrections may be applied in the case of benefits derived from the cancellation of debt. In certain specific situations, the benefits received as a result of the waiver by creditors may be eliminated from the calculation of the qualifying income, resulting in those benefits not being included in the calculation of the top-up tax (i.e. such benefits will therefore not be in scope of the Pillar Two rules). As the conditions of the Pillar Two debt waiver exemption are less lenient than the conditions of the Dutch debt waiver exemption, it is possible that benefits derived from the cancellation of debt are exempt under the Dutch debt waiver exemption but lead to taxation under the Pillar Two rules. However, as described above, the Dutch debt waiver exemption currently in place may also not provide for relief if the taxpayer has tax loss carry forwards available. Therefore, it is important to timely assess the Dutch tax aspects in the event of cancellation of debt by creditors, especially the concurrence between the rules if a debtor is in scope of Pillar Two.

3. Dutch fiscal unity

If a debtor is included in a fiscal unity for Dutch corporate income tax purposes, a debt restructuring may cause such a fiscal unity to terminate as the voting right requirement4 may no longer be met. The latter could occur, for instance, in the context of an enforcement of security rights. The termination of a CIT fiscal unity may have various Dutch tax consequences.

On termination of a fiscal unity, a claw-back mechanism may apply. This claw-back mechanism prescribes that assets with built-in gains (including goodwill) that have been transferred below fair market value within the fiscal unity within a certain period of time (three or six years, depending on the facts) prior to termination of the fiscal unity must be revalued to fair market value on termination at the level of the parent company of the fiscal unity for Dutch corporate income tax purposes. Such upward revaluation would be taxable under the Dutch Corporate Income Tax Act, resulting in additional Dutch corporate income tax being due.

In addition, when a fiscal unity is formed a receivable of a parent company from a subsidiary will not appear on the consolidated balance sheet. This is due to the fact that receivables and payables within the fiscal unity are eliminated for Dutch tax purposes. Therefore, the results on those receivables and value differences related to the receivable and debt do not affect the profit determination of the fiscal unity for as long as such fiscal unity is in place. However, on termination of the fiscal unity, the receivable and debt will revive for Dutch tax purposes and will therefore be included in the balance sheets of the relevant entities. In such a situation, it is prescribed that at the time immediately preceding the time of the termination of the fiscal unity, a receivable should be valued by the creditor at the lower of the nominal value and the value in use. The debtor should, on the other hand, value the debt at nominal value. This prevents the debtor from claiming a taxable loss.

Termination of a fiscal unity may also impact the interest deductibility going forward. Under the earnings stripping rule, interest deductibility generally depends on the adjusted EBITDA. Taxpayers included in a fiscal unity are able to apply this interest deduction limitation on a consolidated basis for the entire fiscal unity, which is generally more beneficial.

4. Concluding remarks

In today's environment, it is important for creditors that have lent funds to a Dutch debtor in financial distress to assess the relevant tax consequences of a debt restructuring at an early stage in the process. Such debt restructuring may significantly impact not only the tax position of such companies, but also the position of the creditor(s). These tax risks may also be considered in the case of a sale of the debtor.

- 1For completeness’ sake, royalties and since 1 January 2024 also dividends are also in scope of the Dutch CWHT (alongside the ‘regular’ dividend withholding tax of 15%; subject to an anti-cumulation rule). For more information, we also refer to our Tax Alert of 4 April 2024.

- 2As listed on the annually updated Dutch list of low tax jurisdictions or the EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions, which includes American Samoa, Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Bahrain, Barbados, Belize, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Fiji, Guam, Guernsey, Isle of Man, Jersey, Palau, Panama, Russian Federation, Samoa, Seychelles, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkmenistan, Turks and Caicos Islands, Vanuatu and the US Virgin Islands.

- 3The principal purpose test will affect tax treaties that are identified as covered tax agreements in the MLI by both treaty partners.

- 4The formation of a fiscal unity for corporate income tax purposes is subject to certain conditions. The main condition is that the parent company holds at least 95% of the shares and voting interest in the subsidiary.